McDonald’s is marking the second year of its NFL league sponsorship with a trio of promotions timed to coincide with the start of the football season. In its first year returning as a league sponsor after a 15-year hiatus, McDonald’s scored well in SportsBusiness Journal's annual NFL sponsor awareness survey. For the first time in five years, more NFL fans correctly identified McDonald’s as the league’s QSR rightsholder. Fans incorrectly identified Subway as the NFL's official QSR in the survey every year since '09. Accordingly, McDonald’s opening-month NFL blitz is larger and portends an expanded effort across a variety of core products, including Chicken McNuggets, French fries, soft drinks, Big Macs, Quarter Pounders, Extra Value Meals and McCafe beverages. Last year’s NFL effort for the fast feeder focused on “Mighty Wings," a temporary menu offering. “We’re looking at this as a season-long opportunity, and a way to engage our customers for the entire season (McDonald’s sponsors balloting for the season-ending Pro Bowl) as opposed to last year, when it was more of an event," said McDonald's Global Marketing Officer Dean Barrett, who added that a return to the ranks of Super Bowl advertisers was uncertain as of yet. McDonald’s early-season NFL promo activity encompasses a photo contest, a tie-in with the latest "Madden" videogame, and packaging with QR codes that unlock exclusive NFL content. The trio of promos will see NFL indicia splashed across more than 180 million fry boxes and more than 120 million soft drink cups. Local team sponsorships have increased to 15, up from 11 last season.

EVERY PICTURE TELLS A STORY: In the QSR’s Tailgate Photo sweepstakes, fans are being asked to post photos via Twitter or Instagram, or with a Vine video displaying “their passion for the NFL and McDonald’s food." Those doing so will be entered in a contest offering the grand prize of having a mobile McDonald's for up to 200 people in their hometown. Weekly prizes will include $100 gift cards to NFLShop.com and subscriptions to NFL Now Plus. The "Madden" NFL tie-in is a "Pick The Play" sweepstakes, through which fans enter by QR code. They are taken to a "Madden" clip in which they can guess the play's outcome. The grand prize is a trip for two to Super Bowl XLIX and a tricked-out game room. A Happy Meal tie-in offers NFL figurines. McDonald's, which shares NFL QSR rights with Papa John's, is leveraging its lead sponsorship of NFL Now with QR codes on NFL-themed 21-ounce soft drink cups, which unlock exclusive content on the OTT network. Support for the promos include dedicated TV ads with a tailgating theme, along with radio, digital and POS. Looking to encourage purchase of McDonald's food for "tailgating anywhere," select markets will sell 20-piece McNugget packs for the discounted price of $5, along with various "bundle packs."

By Terry Lefton

Thursday, September 25, 2014

Wednesday, September 10, 2014

College Football’s New Home

The planning and construction are done. Now can the new College Football Hall of Fame reach its lofty attendance goals?

John Stephenson’s day on this humid August morning started much like every other day, with Stephenson standing in front of a group of well-heeled Atlanta executives explaining why they should visit the new College Football Hall of Fame.The questions that came back from this group of Duke alums at the Buckhead Club ran the gamut. Some wanted to know if the hall could make money — halls of fame are notoriously bad businesses. Others asked how many Blue Devils are in the College Football Hall of Fame.

|

| The $68.5 million project opens this Saturday in Atlanta. |

Stephenson is happy to detail the business model. He doesn’t have the first clue how many Dukies are in the hall.

“People tell me all the time how lucky I am to work in college football,” Stephenson, the hall’s CEO and president, said with a smile. “What I’ve been doing the last 2 1/2 years literally has nothing to do with college football. I’m trying to get a building built.”

Stephenson is almost able to see the final results on Marietta Street in downtown Atlanta, just across from Centennial Olympic Park, the Georgia Aquarium and the World of Coca-Cola.

The college hall spent the past 17 years in South Bend, Ind., but the National Football Foundation, which owns the rights to the hall, decided four years ago to accept an offer from Atlanta organizers. That group, led by Chick-fil-A Peach Bowl President Gary Stokan and Chick-fil-A President Dan Cathy, helped secure the commitment, providing the NFF with a greater platform for its hall and more visibility for the foundation’s scholarship and charitable causes.

Stephenson, formerly an attorney for Atlanta firm Troutman Sanders and a native of the city, took the baton in 2012.

|

The new $68.5 million building will open on Saturday — on schedule and on budget.

He’s especially proud that only $1 million of public money was used. The rest of the building’s cost has been raised through sponsorship dollars and private donations.

“That’s unusual for an attraction like this,” he said, having already ditched the tie from his morning speaking engagement in favor of an open-collar blue shirt and navy jacket.

The hall is down to its last two major pieces of sponsorship inventory, and when those are sold, the attraction will have the commitments it needs to pay off the 94,256-square-foot building.

Now all the hall needs to do is get people inside of it.

Wow factor

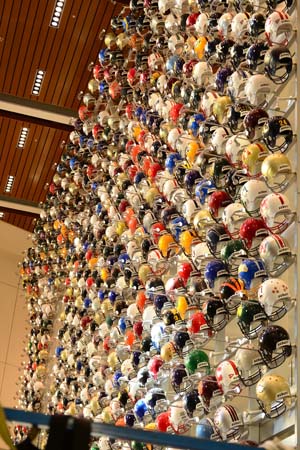

Visitors entering the College Football Hall of Fame will encounter a wall of helmets that’s visually overwhelming. The eyes don’t know where to focus. A touch-screen board enables visitors to find a school, touch an image and light up the helmet.

|

| Visitors are greeted by a massive wall of helmets from every college football program. |

The 768 helmets on the 55-foot-by-30-foot wall represent every school that plays college football, no matter the division. It’s an equal-opportunity display, with the helmets hung randomly. A handful of helmets are generics, placeholders waiting for the next college to start a team.

The hall has worked with helmet-maker Schutt to secure all of the helmets. Two hardworking interns had the chore of putting decals on the side of the helmets.

There’s little question that the wall delivers the wow factor that any attraction hopes for.

“This breaks the mold for sports halls of fame,” said Patrick Gallagher, president and founder of Gallagher & Associates, the Washington, D.C.-based firm that serves as the exhibition designer. Gallagher’s work can be found in any number of museums and exhibits, from the Baseball Hall of Fame to the University of North Carolina’s basketball museum.

The College Football Hall of Fame projects 500,000 visitors a year, an ambitious number compared to the halls for other sports, where 200,000 to 300,000 a year is the norm.

Stephenson looks across Marietta Street and sees more than 2 million people a year visiting the Georgia Aquarium and more than 1 million going to the World of Coca-Cola, so he believes his goal is within reach. The College Football Hall of Fame is right in the middle of all that traffic and the building is literally attached to the Georgia World Congress Center, meaning fans could walk indoors from the hall to the Georgia Dome.

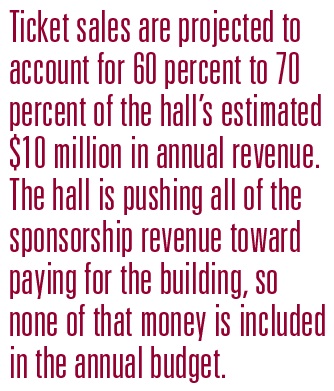

Ticket sales are projected to account for 60 percent to 70 percent of the hall’s estimated $10 million in annual

|

The hall also receives a share of gross revenue from room rentals, catering, retail sales and parking in the adjacent deck.

Omni, the hotel next door, is the catering partner, while California-based Event Network Inc. will operate the hall’s retail store. Event Network also runs the store inside the Georgia Aquarium.

ESPN, while not officially a partner, worked with the hall on connectivity throughout the building.

“Where does the fiber need to run? Where should the camera plug-ins be? Those are the areas where ESPN really helped us,” Stephenson said.

Integrating sponsors

As visitors advance up the stairs to the second floor, they are greeted by a 52-foot-long touch-screen display, where fans can find their favorite teams, players and moments.

A staff of 35 full-time fan ambassadors and 35 more part-timers will browse through the exhibits, looking for opportunities to show guests how certain interactive displays work.

The galleries are a blend of historical artifacts, like the trombone from the Stanford band that was trampled during “The Play,” mixed with the latest in interactives.

The hall brought in Cortina Productions to create a variety of interactives, enabling visitors to virtually paint their face, diagram Xs and Os, sing the fight song or call the play for memorable moments. Photos and other keepsakes can be accessed through the hall’s official website, cfbhall.com.

|

| Southwest Airlines sponsors a tunnel that leads to a 45-yard playing field. |

It’s “items and imagery,” as Brad Olecki, vice president of business development, likes to say.

Olecki primarily has been responsible for integrating the hall’s sponsors into the displays, either through branding or product placement, without it becoming too overwhelming. Founding partners AT&T, Chick-fil-A, Chick-fil-A Peach Bowl, Coca-Cola and Kia have their brands tastefully etched in brushed stainless steel around the second floor.

Coke sponsors a gallery on game-day traditions. Kia brought in a specially designed car with a drop-down TV and built-in grill for tailgating. Chick-fil-A, the hall’s presenting sponsor, has its name on multiple elements.

The two major spaces remaining without a sponsor are the 150-seat theater and the 45-yard field with a goalpost.

|

Stephenson and Olecki spearhead sales, with an assist from Fishbait Marketing’s Rick Jones.

The hall wouldn’t comment on the value of specific deals, but the 15 sponsorships sold so far went for a wide range, starting in the mid-to-high six figures for official partners to more than seven figures a year.

Founding partners have significant integration and product placement throughout. Other official partners had the opportunity to put their name on pieces of the building, like the Southwest Airlines Touchstone Tunnel, which leads from the lobby to the 45-yard playing field.

“The designers really let the partners have a voice as they were going through the process, which I think is unique,” Olecki said.

‘Our building is a big show’

The final flight of stairs ascends to the third floor, which is reserved for the actual hall of fame. The stone floors,wood walls and light hum of white noise send the message that this floor is different from the other two.

Rather than the busts that are so often associated with halls of fame, this one lists each class year-by-year.

Huge 6-foot-tall video displays show images, highlights and stats for the hall of famer selected, and the display swivels, enabling the visitor to see multiple angles as images of the player come to life.

Hall organizers thought the more contemporary displays fit the theme of the building more so than the traditional busts.

“This is the nicest room in the building,” Stephenson said as he proudly walked the hall of fame room.

The hall of fame is the room of reverence for the game’s greats, but it is, after all, just a segment of the overall project.

|

| Hall of Fame CEO and President John Stephenson is eager to get down to business. |

Organizers named it the College Football Hall of Fame and Chick-fil-A Fan Experience for a reason. They want to send the message that there’s a lot more inside than the ring of honorees.

“I’m building a big stage for the hall, which is the NFF’s deal,” Stephenson said. “My job is to build this building and start this business.

“We’re not just in the hall of fame business, we’re in the attraction business. We’re in the entertainment business.

Our building is a big show. We’re going to sell you a ticket to see something you can’t see anywhere else. Yes, the hall of fame is in our building, but most of the building is an attraction on par with what is around us.”

By Michael Smith |

Wednesday, August 27, 2014

Sports Paradox: America's Regulated Economy vs. Europe's Free Market

In the States, fairness rules allow underdog teams to lure superstars like LeBron James. Across the Atlantic, powerful franchises are only getting more powerful.

Last week in America, LeBron James went back to the Cleveland Cavaliers. A lot of people saw it as a victory for American values, a victory for the little guy and for old-fashioned fairness. LeBron is going back to play for his hometown! No more of this teaming-up-with-other-stars-to-make-a-superteam nonsense! Finally, finally, small-market Cleveland might win a title!This week in Europe, Premier League soccer giants Manchester United signed a jersey deal with Adidas worth around 75 million pounds ($128 million) per year. That money—which is separate, by the way, from the 53 million pounds per year Chevrolet has agreed to pay to plaster its logo across the jersey’s chest—is more than double the size of the next nearest “kit deal,” Arsenal’s with Puma. And it’s more than the total revenue of nine of the Premier League’s 20 clubs in the year 2011-2012. In short, some soccer teams in Europe are relatively poor, and some are very, very rich.

While the Germans were celebrating their nation’s World Cup triumph, some of those very rich clubs were busy figuring out which poorer ones were unfortunate enough to have a player perform well at the tournament. Can little Real Sociedad afford to keep the promising French winger Antoine Griezmann? Has Russian billionaire owner Dmitry Rybolovlev gotten bored with his new plaything Monaco FC yet? Real Madrid would be happy to take Colombia wonderkid James Rodriguez off his hands. Premier League overachievers Southampton had three English stars snapped up by Liverpool and Manchester United before a ball was even kicked in Brazil.

The Lebron signing and the Adidas deal took place days apart by coincidence, but I could have picked nearly any week and found clear illustrations of the counterintuitive gap between the sporting rules and cultures in Europe and America. In wild, wild, Western Europe, anything goes. Unregulated capitalism is matched by unfettered competition. In the U.S., the major team sports are highly redistributive, or even socialistic.

For example:

- American teams share a great deal of their revenue in the name of competitive balance. Unprofitable teams are propped up by the big guys. European soccer’s nascent Financial Fair Play regulatory system is largely toothless, and clubs can spend what they please on their players—pushing many a small club that tries to keep up into bankruptcy.

- Most European soccer leagues operate on a promotion/relegation system, meaning at the end of the season the three last-placed teams are sent to a lower division and replaced by the three top teams from the division below. Contrarily, American teams are rewarded for a poor season by getting the best chance to select college’s top player. The NBA is even contemplating a new draft system to discourage teams from intentionally losing games.

- The NFL, NHL, and NBA all use a salary cap in the name of competitive balance; MLB has implemented a luxury tax with the same goal in mind. European clubs largely eschew trades in favor or buying and selling stars for up to nine-figure fees. Wealthy clubs, like oligarch Roman Abramovich’s Chelsea FC, buy and stash dozens of young players in the lower leagues, recalling them if the players prove themselves talented or salable.

- Every American league has more parity than the big soccer leagues of Spain, Italy, and England. Small-time clubs have no chance of winning the league title. They don’t even pay lip-service to the impossible dream; fans can hope only for an upset or two and the right to do it all again next year—that is, if they can avoid relegation. The top finishers from each country play in a money-spinning competition called the Champions League.

Still, the configuration seems incongruous, considering that socialism is a dirty word for many Americans, and how much more robust Europe’s welfare state is. And sports inequality has virtues that would seem to appeal to Americans. The continued dominance of the few ensures the best rivalries rage on for years, much like the UNC vs. Duke and Michigan vs. Ohio State battles that liven up college sports. Relegation scraps mean every team can celebrate something, and the combination of the hierarchical system and free-spending owners allows improbable rises up the division ladder—the aforementioned overachievers at Southampton were languishing in English football’s third tier just a few years ago. Imagine the AA Wichita Wingnuts making a deep MLB playoff run! And Americans love watching the improbable. European tournaments like England’s FA Cup throw hundreds of teams of all sizes into one knockout tournament. It’s March Madness, Texas-sized.

But the charms of America’s more-egalitarian system are clear enough. Every major region gets a major sports team, and those teams are given a legitimate chance to win a title. The football team from Green Bay has as many Super Bowl titles as the Giants of New York. That’s impossible in Europe, where the powerhouses from Barcelona and Madrid have won 64 of 83 Spanish league titles. The players here are spread out pretty fairly as well. Only in America can LeBron James go back home to the country’s 45th largest city and make just as much as the salary-capped Los Angeles Lakers could afford to pay him.

This state of affairs came about long ago, and isn’t likely to change soon. The NFL got an anti-trust waiver from Congress to establish its revenue-sharing system in 1961, while the English Premier League’s predecessor, The Football League, has been around in various unregulated guises since 1888.

Which system is “better?” It’s probably not worth arguing about. While inequality and player-poaching evoke some Jacobin outrage in Europe, much like some wealthy American football owners don’t like sharing, all of these sports are broadly profitable and widely popular. Which system is more “American?” Well, America’s spirit is famously two-sided. The answer depends whether you ask Eugene Debs or Joseph McCarthy, Alexander Hamilton or Thomas Jefferson, Dan Gilbert or Pat Riley. It’s all good sports. Let’s just keep watching.

By: Noah Gordon

Tuesday, August 26, 2014

Pitbull: Get Rich or Die Shilling

Pitbull, born Armando Pérez, self-titled Mr. Worldwide, and often known simply as Pit, slides into his seat at a hotel restaurant about 25 minutes inland from South Beach. The place is well outside the Miami party scene and its paparazzi, and is either purposefully retro—deco chairs, white tablecloths, a waitress who must be 80 wearing bright coral lipstick—or hasn’t been updated in 50 years. It’s empty save for one of the biggest pop stars in the world and a group of his associates, all wearing suits, and clustered at two tables. Pitbull taps his water glass, and the waitress hurries over to fill it. His lawyer, Leslie Zigel, hands him an agenda, which offers topics like “Endorsement Deal Matters,” “Investments,” and, in capital letters, “DISRUPTION.”

Zigel and Pitbull started working together in 2010, after Pitbull closed his first major sponsorship deal, with Dr Pepper, which Zigel was representing at the time. “He told me he appreciated my approach to dealmaking and asked if I would consider joining his team,” says Zigel. “I’m a jazz bass player, and he liked that I thought like a musician, not a typical lawyer.” Zigel looks like Stanley Tucci and speaks to Pitbull encouragingly, like a cheerful high school gym teacher.

Zigel and Pitbull started working together in 2010, after Pitbull closed his first major sponsorship deal, with Dr Pepper, which Zigel was representing at the time. “He told me he appreciated my approach to dealmaking and asked if I would consider joining his team,” says Zigel. “I’m a jazz bass player, and he liked that I thought like a musician, not a typical lawyer.” Zigel looks like Stanley Tucci and speaks to Pitbull encouragingly, like a cheerful high school gym teacher.

He’s Touched Down Everywhere

Cars: In a series of Spanish and English ads for the Dodge Dart. En Español: “Cómo hacer un auto.” Beer: Stars in two Bud Light ads as part of a multicultural campaign. Both spots take place in a club and feature his song Bon Bon (“Don’t stop the paaaarty!”). Soda: Appears in a Dr Pepper TV ad titled “Dream,” about making it as an immigrant. “I’m Pitbull, and I’m one of a kind.”

After discussing a few of Pitbull’s investments—a restaurant chain called Miami Subs Grill that’s undergoing storefront renovations and a water filtration system called EcoloBlue that Pitbull believes will be a “game changer”—the rapper moves down to “Meetings” and says, “Let’s do Bitcoin.”

Zigel slides over a stack of articles about Bitcoin and mentions a possible sitdown with Merlin Kauffman, who runs a $7.5 million Bitcoin investment fund focused on the hardware that runs the currency. Pitbull flips through the pages quickly, not displaying much interest. In public, Pitbull is rarely seen without an enormous pair of aviator-style sunglasses, but he’s left them off for this meeting. His exposed eyes are ocean-colored, surrounded by little-girl lashes. Freckles dot his nose. There’s a Twitter joke that compares a picture of Pitbull to Lord Voldemort, and while uncharitable, there’s something to it, with that crowded, leonine smile and menacing cannonball-like head.

“I still want to know, what exactly is Bitcoin?” Pitbull says. “How real is it? Is it going to be adopted and be disruptive?”

“The people who are going to adopt it are young,” Zigel replies. “If it’s something they decide they want to do, it’s going to be a force to be reckoned with.”

“What makes this real money?”

Zigel, looking unsure, glances quickly at the articles Pitbull has shoved back toward him. “It’s very speculative right now,” he says. “There’s nothing that’s holding it together.”

Pitbull is dubious. “No gold, no nothing?”

“No banks behind it, no.”

“Are they having problems with the streets?”

Zigel’s eyebrows rise. Pitbull may be referring to the financial markets, or he may be referring to streets of a grittier variety. Pitbull, 33, spent much of his life navigating them, as he’s quick to mention. He’s a first-generation American whose parents came to Miami from Cuba, his mother in the 1960s as part of Operation Pedro Pan—Miami’s effort to get children out of the communist country—and his father in 1980. Armando Sr. was a low-level criminal and drug dealer; he met Pitbull’s mother while she was what Pitbull calls a “burlesque dancer.” By the time Pitbull was a teenager and trying to make it as a musician, he’d dropped out of school and was dealing drugs. In 2001 he hooked up with successful rapper Lil Jon and producer Luther Campbell, the frontman for 2 Live Crew, and in 2004 released his first album, M.I.A.M.I. It featured the single Culo, which peaked at No. 32 on the Billboard Hot 100. Culo, which translates, roughly, to “ass,” is what’s referred to as reggaeton—an upbeat sound that combines hip-hop, Jamaican dancehall, and more traditional Latino music such as salsa. In it, Pitbull raps in English and Spanish, and his style is hypnotizingly monotone, making it an ideal counterpart for a great hook.

In the decade since, Pitbull has become ubiquitous and is moving into the territory of empire builder, along the lines of 50 Cent or Jay Z. His publicist, Tom Muzquiz, a peppy man with spiky hair who’s lingering at the next table, promised to figure out the perfect day for us to spend together to help me understand his boss’s reach and ambition. And it didn’t involve a yacht or a crazy night out in South Beach or anything to do with his outsize lifestyle. Exciting for Pitbull, now, is thinking about things other than partying, studio time, and ladies. (He has six children with an undisclosed number of women.)

This hotel restaurant isn’t just where Pitbull asked to meet on this day, it’s where he conducts business; he doesn’t have a normal office, so he holds meetings here, sometimes jumping from one table to the other. The location is perfect for Pitbull, as it’s private enough but doesn’t deny him the pleasure of a Greek chorus of Yes Men. He asks that I keep it a secret. If it gets out, Muzquiz says, “it could create problems.” Along with Zigel and Muzquiz, the group consists of Pitbull’s manager, Mike Calderon, and a few large, intimidating men whose purpose seems to be laughing when Pitbull tells a joke. At one point someone’s phone goes off. The ringtone is Timber, Pitbull’s most recent No. 1 hit, which features Kesha singing, “It’s going down, I’m yelling Timber!” Pitbull rolls his eyes.

Even if you don’t know who Pitbull is, you do. You’ve danced to a Pitbull song at a wedding or seen him in a commercial. He’s sold more than 5 million albums worldwide in an era when people hardly buy albums, and his YouTube videos have exceeded 5 billion views. He’s had nine top 10 singles internationally, including No. 1 hits such as 2011’s Give Me Everything, featuring the R&B artist Ne-Yo. He’s sold out numerous world tours and is teaming up in the fall with Enrique Iglesias. He’s an endorsement machine, chalking up deals with Dodge, Bud Light, and Kodak. Like many hip-hop stars, he owns a vodka brand. His is called Voli—it’s low-calorie.

His songs are contagious, the kind of poppy club tunes that DJs play to get everyone on the floor. On his own, he’s OK, but Pitbull’s real success comes from collaborations with other artists—song co-headliners include Usher, Chris Brown, T-Pain, Marc Anthony, Jennifer Lopez, Christina Aguilera, and Pharrell Williams, among others. They sing the hooks, Mr. Worldwide raps through the bridge, and suddenly everyone’s hands are in the air. He is expert at gathering up talent, and then packaging and producing the final product. Pitbull’s got this thing of yelling “Dale!” during his songs, which means, “Go ahead!” or “Do it!” or “Give it!” It’s become a rallying cry for his fans, a kind of F-U to music snobs who might discount the rapper’s slightly pedestrian rhymes. People want to have fun. Pitbull knows how to deliver it.

Accordingly, Pitbull is rich. Estimates of his wealth range from $10 million to $20 million, most of that coming from endorsement deals with huge American companies. Corporations have decided that he’s the answer to landing Latino customers. In 2012 the Latino population in the U.S. was 53 million, a 50 percent increase from 2000, according to the Pew Research Center. Latinos now account for 17 percent of the U.S. population and collectively spend more than $1.3 trillion each year, according to Nielsen. In the past month, brands such as Hyundai, ESPN, and Corona have unveiled national ads entirely or partly in Spanish. Colombian actress Sofia Vergara is now one of America’s best-paid endorsers, with high-profile deals with Kmart, Diet Pepsi, and CoverGirl . Singer Shakira, also from Colombia, appears in ads for Dannon, Pepsi, and T-Mobile, and just signed a deal with Oral-B and Crest. Actresses Eva Longoria and Jessica Alba star in far more commercials than their middling careers suggest they should. Companies are scrambling to win this demographic, and Pitbull is eager to help them.

Being Mr. Worldwide does take a toll, though. In his restaurant office, he’s constantly downing water. When the glass is empty, his eyes get manic. He’s jittery, jangly, as if he’s always about to jump up and run away. He looks 10 years older than he should, and his Miami Vice-inspired clothes don’t help. For performances and public appearances, Pitbull wears black or white suits, sometimes with a tie, always with those aviators. Today he’s in a blue pinstripe jacket and blue vest, the buttons straining a bit against his stomach.

He gets up, returns, is ready to discuss the next thing, younow.com, a video startup, somewhere between Twitter and YouTube, that allows users to comment on videos as they watch them. His many partnerships and deals are brought to him, he says, by everyone—his team, his investors, himself. “Some people have amazing ideas, but nobody knows about them,” he says. “I partner with companies and say, ‘You get here, then we’ll step on the gas.’ ” He says he takes a rigorous approach to evaluating these possibilities. He does market-testing with children. “I get these companies to go to the schools and say to the kids, ‘What do you think about this? Do you think it’s cool?’ Then they’ll start using it, and say, ‘Did you think about this?’ ” He says he wants to be a billion-dollar brand in the next three years. That’s a long shot—neither Jessica Simpson nor the Kardashians are worth that much, though they both claim to be.

Pitbull and Zigel discuss his YouNow appearance on May 28, when he announced his partnership with entertainment and TV production company Endemol. This is what Pitbull excels at: using one of his businesses to promote another. Zigel says the test went well and user engagement was high. Pitbull has 16.9 million followers on Twitter and more than a million on Instagram (FB), believes in his own promotional power, and has had, as much as anyone in the pop-culture landscape, success in convincing others of it, too.

In 2013, Chrysler signed Pitbull to help launch its latest entry in the compact-car segment, the Dodge Dart. Pitbull did two commercials for the car, one in English, one in Spanish, featuring him driving and offering the monumental swagger that has become his trademark. (In an ad for Bud Light, he makes an art form of merely walking through a crowd, capped off by what might be described as an epic lowering of a pair of sunglasses, followed by an historic grin.)

Photograph by Christopher LeamanPitbull gets mic’d up for a July 7 interview on Univision

Photograph by Christopher LeamanPitbull gets mic’d up for a July 7 interview on Univision

Juan Torres, head of multicultural advertising for Chrysler Group, says Pitbull draws two different kinds of consumers: millennials and Hispanics. “Hispanics are not only brand-loyal consumers but are loyal to this particular car segment. So in that case, the strategic alignment with Pitbull made sense,” he says. “And when you start to peel back the layers, you see that 43 percent of millennials are multicultural, and so you have this incredible artist who resonates with all these different demographics.” Torres says that since the commercials aired, the Dart has steadily gained market share, with 20 percent of its buyers consisting of multicultural consumers.

Zigel and Pitbull move on to a proposed book, which they hope will create a bidding war among publishing houses. The title will likely be From a Negative to a Positive. “It’s based on my motto,” explains Pitbull. “Since my mother started playing Tony Robbins when I was in the fifth grade, I’ve applied that to my life and career. It’s not only a business strategy, it’s for everything.”

“The book is just the first piece,” offers Zigel. They’re thinking of a self-help lifestyle brand, with Pitbull in the Robbins role.

He and Zigel discuss the possibility of investing in Vevo, the video hosting service that’s co-owned by Universal Music Group, Google (GOOG), Sony Music, and Abu Dhabi Media. Zigel has made Pitbull a flowchart of online streaming revenue, showing how artists and labels make money off video views. Pitbull studies it, squinting. Finally, he says, “I don’t understand this. I see a lot of f---ing arrows, and only two f---ing arrows to the artist. Something’s wrong.”

Next up: a premium sake called Rock Sake, which aims to make the Japanese rice wine cool—like, bottle-service cool. Pitbull’s interested, but he wants to get Playboy Enterprises, with whom he has a strategic partnership, involved. Playboy’s waffling. “Scott isn’t necessarily on board,” says Zigel, referring to Playboy Chief Executive Officer Scott Flanders.

Flanders, who ran Macmillan Publishers and Columbia House before joining Playboy in 2009, anointed Pitbull the company’s artist-in-residence last year. “First we did our own brand tracking, and he had the lowest negative scores of any superstar that was in our constellation of consideration,” says Flanders, whose mission is to turn Playboy into a lifestyle brand that appeals to millennials. “We were quite surprised—anyone with a rapper background will have passionate fans but also detractors.” Playboy brought in PR and research firm Edelman to do an independent study on the star’s appeal. “They found that the overlap of attributes that people associated with Pitbull and Playboy was significant, and we got a forceful recommendation to proceed with striking a relationship.”

The seven-figure deal grants Pitbull fees as a brand ambassador as well as a “substantial” percentage of revenue from any licensed products. So far, Flanders is thrilled with the collaboration. “The interest from licensees has been staggering,” he says. “We had no idea how hot he is in countries like India, where we’re now doing deals. I talked to him about that, and he said, ‘Oh yeah, I’m hot there, and South America, too.’ So we went to Mexico.”

Zigel’s time is up. He stands, shakes hands all around, and goes back to the table of associates, where he does a kind of tag-team maneuver with Calderon, who’s next in line.

“The first day broke $13 grand, which is great,” says Calderon. “Because there wasn’t any advertisement for it, only on Twitter and Instagram.”

“Wow!” says Pitbull, before downing another glass of water. “You really need to keep an eye on that bad boy. That’s your call to action! Now we come back and say, ‘Look, our people, we know how to move ’em, and this is the kind of things we can do.’ Congrats on that.”

With Pitbull’s shiny tie and fuzzy, rapper-turned-entrepreneur-speak—everything’s a “call to action,” a “no-brainer,” or has to do with “monetizing” something or other—it’s easy to underestimate him. But Pitbull’s longtime music manager, Charles Chavez, says the smartest thing about Pitbull is that he knows what he doesn’t know. He’s gotten opportunities because of his music and has surrounded himself with advisers. And he keeps making more money. “He’s just more intelligent than the average artist,” says Chavez. “He’s always watching Bloomberg TV! It’s an ego-driven business, and most artists, it’s all about them. He understands he can’t do everything himself, and he soaks everything in.”

Calderon is done; next arrives Fernando Zulueta, a barrel-chested, deep-voiced businessman who works with Pitbull on his Miami charter school project. Zulueta has gray hair, a deep tan, and a large glass of red wine. Pitbull will be running his own New Year’s Eve special on Fox, and Zulueta suggests hiring the Black Eyed Peas for the night. They move on to a startup, a kind of Spanish-language YouTube, which Zulueta promises will be like Pitbull’s own TV station. Pitbull considers this and waves at the waitress for more water. The look on his face suggests he’s about to say something profound, and he delivers.

“Culture is generation. Generation is power.”

“Explain that to me—because you use generators to make power, right?” Zulueta laughs with a loud bark.

Pitbull continues, straight-faced. “When you become a generation—say, the MTV generation—that’s where you create your power.”

Zulueta purses his lips, trying to understand.

“The content fed the culture, the culture fed the generation. Everyone says content is king. But culture is everything. Content creates a culture—the Kardashians created a culture.”

“I got it,” says Zulueta, though it seems like he might not.

Pitbull has already moved on. In a few hours, he’s due to get an honorary degree from Miami’s Doral College and has to deliver an inspirational speech. Zulueta hands over a draft. It’s about 20 pages, and the type is huge. Even so, Pitbull is displeased. “This is too long,” he says, flipping through. “This isn’t me. I need this to be the real me.” Zulueta assures him he can do whatever he wants to the speech, and at that Pitbull goes upstairs—to a room? an office?—to edit the speech with Muzquiz. Over the next two hours, one by one, Pitbull’s associates leave, until it’s just me and the ancient waitress.

When Muzquiz finally comes down, he’s apologetic but explains the speech needed work. We head to the college. Instead of an Escalade or limo, there’s just a regular midsize sedan. Pitbull, sunglasses finally on, gets in, and a cloud of cologne fills the small car. He hammers away on his BlackBerry. “It’s just me and the president who use these now,” he jokes. He’s rereading his speech on the phone and seems a little nervous.

It’s silent except for when he gives his driver directions in Spanish and tells one of his guys that he’s ready for his iced coffee. As we near the school in central Miami, Pitbull starts spraying himself with more cologne. First his Pitbull fragrance, then a bit of Tom Ford, then some Pitbull again. He explains, “I mix it, and then depending on how the women react, I either mix the same ones again or try a different combination.”

On arrival at Doral, Pitbull is whisked away to don his graduation robes. His appearance is supposed to be a surprise, though some members of the local Miami press have found out. They always do—he’s their most famous son right now, and the city loves him. Reporters line up at the back door, waiting.

Doral is both a charter high school and a tiny college, and there are probably 300 attendees in the auditorium, parents and grandparents fanning themselves with programs. Intros are made, and a very sweet high schooler gives a speech about how “this isn’t the end, it’s just the beginning.” Then Zulueta gets up to introduce the mystery guest and recipient of Doral’s first honorary degree.

He speaks of this person’s generosity and business acumen, and when he talks about his status as an international pop star, the crowd begins to buzz. Younger siblings elbow each other, and grandmothers sit up straighter. Pitbull comes out in his robe, waving and beaming, and everyone screams and whistles and whoops. He prances around the stage, enjoying it, his robe flowing behind him as he paces. The crowd finally quiets, and his speech begins.

“I did what they said I couldn’t. I became what they said I wouldn’t, and because of very special people in my life who believed in me, that’s why I’m on this stage tonight.” Applause. “So with that said, I want to say thank you to my mother.” More applause, mostly from the women. “She’s someone who had to raise a man, a woman who made a man. But she’s someone who taught me the No. 1 lesson in life, which is: how to survive.”

On paper, it’s inspirational gibberish. But Pitbull’s delivery—the neat pauses between each clause, his staccato cadence—transcends the clichéd subject matter. The crowd is in it with him, rising and falling as he slows down and speeds up: He’s turned it into a radio-worthy rap. The 20-minute oration culminates in a rousing call to let loose: “I know you’re going to get off the chain, off the glass, off the flip, off the rip, off the everything, y’all going to turn it up.” There’s a term in electronic dance music called dropping the bass—it’s that moment when, after a brief letup, the beat returns full force, and everyone goes insane. The audience is waiting for him to finish, waiting for the bass to drop. And then it comes. “Y’all go to all the parties you want to go to, and I’m sure there’s going to be plenty of them. But there’s no party like this, right here, right now.” He is theirs, and they are his.

By Emma Rosenblum

After discussing a few of Pitbull’s investments—a restaurant chain called Miami Subs Grill that’s undergoing storefront renovations and a water filtration system called EcoloBlue that Pitbull believes will be a “game changer”—the rapper moves down to “Meetings” and says, “Let’s do Bitcoin.”

“I still want to know, what exactly is Bitcoin?” Pitbull says. “How real is it? Is it going to be adopted and be disruptive?”

“The people who are going to adopt it are young,” Zigel replies. “If it’s something they decide they want to do, it’s going to be a force to be reckoned with.”

“What makes this real money?”

Zigel, looking unsure, glances quickly at the articles Pitbull has shoved back toward him. “It’s very speculative right now,” he says. “There’s nothing that’s holding it together.”

Pitbull is dubious. “No gold, no nothing?”

“No banks behind it, no.”

“Are they having problems with the streets?”

Zigel’s eyebrows rise. Pitbull may be referring to the financial markets, or he may be referring to streets of a grittier variety. Pitbull, 33, spent much of his life navigating them, as he’s quick to mention. He’s a first-generation American whose parents came to Miami from Cuba, his mother in the 1960s as part of Operation Pedro Pan—Miami’s effort to get children out of the communist country—and his father in 1980. Armando Sr. was a low-level criminal and drug dealer; he met Pitbull’s mother while she was what Pitbull calls a “burlesque dancer.” By the time Pitbull was a teenager and trying to make it as a musician, he’d dropped out of school and was dealing drugs. In 2001 he hooked up with successful rapper Lil Jon and producer Luther Campbell, the frontman for 2 Live Crew, and in 2004 released his first album, M.I.A.M.I. It featured the single Culo, which peaked at No. 32 on the Billboard Hot 100. Culo, which translates, roughly, to “ass,” is what’s referred to as reggaeton—an upbeat sound that combines hip-hop, Jamaican dancehall, and more traditional Latino music such as salsa. In it, Pitbull raps in English and Spanish, and his style is hypnotizingly monotone, making it an ideal counterpart for a great hook.

In the decade since, Pitbull has become ubiquitous and is moving into the territory of empire builder, along the lines of 50 Cent or Jay Z. His publicist, Tom Muzquiz, a peppy man with spiky hair who’s lingering at the next table, promised to figure out the perfect day for us to spend together to help me understand his boss’s reach and ambition. And it didn’t involve a yacht or a crazy night out in South Beach or anything to do with his outsize lifestyle. Exciting for Pitbull, now, is thinking about things other than partying, studio time, and ladies. (He has six children with an undisclosed number of women.)

This hotel restaurant isn’t just where Pitbull asked to meet on this day, it’s where he conducts business; he doesn’t have a normal office, so he holds meetings here, sometimes jumping from one table to the other. The location is perfect for Pitbull, as it’s private enough but doesn’t deny him the pleasure of a Greek chorus of Yes Men. He asks that I keep it a secret. If it gets out, Muzquiz says, “it could create problems.” Along with Zigel and Muzquiz, the group consists of Pitbull’s manager, Mike Calderon, and a few large, intimidating men whose purpose seems to be laughing when Pitbull tells a joke. At one point someone’s phone goes off. The ringtone is Timber, Pitbull’s most recent No. 1 hit, which features Kesha singing, “It’s going down, I’m yelling Timber!” Pitbull rolls his eyes.

Even if you don’t know who Pitbull is, you do. You’ve danced to a Pitbull song at a wedding or seen him in a commercial. He’s sold more than 5 million albums worldwide in an era when people hardly buy albums, and his YouTube videos have exceeded 5 billion views. He’s had nine top 10 singles internationally, including No. 1 hits such as 2011’s Give Me Everything, featuring the R&B artist Ne-Yo. He’s sold out numerous world tours and is teaming up in the fall with Enrique Iglesias. He’s an endorsement machine, chalking up deals with Dodge, Bud Light, and Kodak. Like many hip-hop stars, he owns a vodka brand. His is called Voli—it’s low-calorie.

His songs are contagious, the kind of poppy club tunes that DJs play to get everyone on the floor. On his own, he’s OK, but Pitbull’s real success comes from collaborations with other artists—song co-headliners include Usher, Chris Brown, T-Pain, Marc Anthony, Jennifer Lopez, Christina Aguilera, and Pharrell Williams, among others. They sing the hooks, Mr. Worldwide raps through the bridge, and suddenly everyone’s hands are in the air. He is expert at gathering up talent, and then packaging and producing the final product. Pitbull’s got this thing of yelling “Dale!” during his songs, which means, “Go ahead!” or “Do it!” or “Give it!” It’s become a rallying cry for his fans, a kind of F-U to music snobs who might discount the rapper’s slightly pedestrian rhymes. People want to have fun. Pitbull knows how to deliver it.

Accordingly, Pitbull is rich. Estimates of his wealth range from $10 million to $20 million, most of that coming from endorsement deals with huge American companies. Corporations have decided that he’s the answer to landing Latino customers. In 2012 the Latino population in the U.S. was 53 million, a 50 percent increase from 2000, according to the Pew Research Center. Latinos now account for 17 percent of the U.S. population and collectively spend more than $1.3 trillion each year, according to Nielsen. In the past month, brands such as Hyundai, ESPN, and Corona have unveiled national ads entirely or partly in Spanish. Colombian actress Sofia Vergara is now one of America’s best-paid endorsers, with high-profile deals with Kmart, Diet Pepsi, and CoverGirl . Singer Shakira, also from Colombia, appears in ads for Dannon, Pepsi, and T-Mobile, and just signed a deal with Oral-B and Crest. Actresses Eva Longoria and Jessica Alba star in far more commercials than their middling careers suggest they should. Companies are scrambling to win this demographic, and Pitbull is eager to help them.

Being Mr. Worldwide does take a toll, though. In his restaurant office, he’s constantly downing water. When the glass is empty, his eyes get manic. He’s jittery, jangly, as if he’s always about to jump up and run away. He looks 10 years older than he should, and his Miami Vice-inspired clothes don’t help. For performances and public appearances, Pitbull wears black or white suits, sometimes with a tie, always with those aviators. Today he’s in a blue pinstripe jacket and blue vest, the buttons straining a bit against his stomach.

He gets up, returns, is ready to discuss the next thing, younow.com, a video startup, somewhere between Twitter and YouTube, that allows users to comment on videos as they watch them. His many partnerships and deals are brought to him, he says, by everyone—his team, his investors, himself. “Some people have amazing ideas, but nobody knows about them,” he says. “I partner with companies and say, ‘You get here, then we’ll step on the gas.’ ” He says he takes a rigorous approach to evaluating these possibilities. He does market-testing with children. “I get these companies to go to the schools and say to the kids, ‘What do you think about this? Do you think it’s cool?’ Then they’ll start using it, and say, ‘Did you think about this?’ ” He says he wants to be a billion-dollar brand in the next three years. That’s a long shot—neither Jessica Simpson nor the Kardashians are worth that much, though they both claim to be.

Pitbull and Zigel discuss his YouNow appearance on May 28, when he announced his partnership with entertainment and TV production company Endemol. This is what Pitbull excels at: using one of his businesses to promote another. Zigel says the test went well and user engagement was high. Pitbull has 16.9 million followers on Twitter and more than a million on Instagram (FB), believes in his own promotional power, and has had, as much as anyone in the pop-culture landscape, success in convincing others of it, too.

In 2013, Chrysler signed Pitbull to help launch its latest entry in the compact-car segment, the Dodge Dart. Pitbull did two commercials for the car, one in English, one in Spanish, featuring him driving and offering the monumental swagger that has become his trademark. (In an ad for Bud Light, he makes an art form of merely walking through a crowd, capped off by what might be described as an epic lowering of a pair of sunglasses, followed by an historic grin.)

Photograph by Christopher LeamanPitbull gets mic’d up for a July 7 interview on Univision

Photograph by Christopher LeamanPitbull gets mic’d up for a July 7 interview on UnivisionJuan Torres, head of multicultural advertising for Chrysler Group, says Pitbull draws two different kinds of consumers: millennials and Hispanics. “Hispanics are not only brand-loyal consumers but are loyal to this particular car segment. So in that case, the strategic alignment with Pitbull made sense,” he says. “And when you start to peel back the layers, you see that 43 percent of millennials are multicultural, and so you have this incredible artist who resonates with all these different demographics.” Torres says that since the commercials aired, the Dart has steadily gained market share, with 20 percent of its buyers consisting of multicultural consumers.

“The book is just the first piece,” offers Zigel. They’re thinking of a self-help lifestyle brand, with Pitbull in the Robbins role.

He and Zigel discuss the possibility of investing in Vevo, the video hosting service that’s co-owned by Universal Music Group, Google (GOOG), Sony Music, and Abu Dhabi Media. Zigel has made Pitbull a flowchart of online streaming revenue, showing how artists and labels make money off video views. Pitbull studies it, squinting. Finally, he says, “I don’t understand this. I see a lot of f---ing arrows, and only two f---ing arrows to the artist. Something’s wrong.”

Next up: a premium sake called Rock Sake, which aims to make the Japanese rice wine cool—like, bottle-service cool. Pitbull’s interested, but he wants to get Playboy Enterprises, with whom he has a strategic partnership, involved. Playboy’s waffling. “Scott isn’t necessarily on board,” says Zigel, referring to Playboy Chief Executive Officer Scott Flanders.

Flanders, who ran Macmillan Publishers and Columbia House before joining Playboy in 2009, anointed Pitbull the company’s artist-in-residence last year. “First we did our own brand tracking, and he had the lowest negative scores of any superstar that was in our constellation of consideration,” says Flanders, whose mission is to turn Playboy into a lifestyle brand that appeals to millennials. “We were quite surprised—anyone with a rapper background will have passionate fans but also detractors.” Playboy brought in PR and research firm Edelman to do an independent study on the star’s appeal. “They found that the overlap of attributes that people associated with Pitbull and Playboy was significant, and we got a forceful recommendation to proceed with striking a relationship.”

Zigel’s time is up. He stands, shakes hands all around, and goes back to the table of associates, where he does a kind of tag-team maneuver with Calderon, who’s next in line.

“I partner with companies and say, ‘You get here, then we’ll step on the gas.’ ”Calderon is small and smiley, with a Latin accent and a suit that looks about two sizes too big for his skinny neck. As Pitbull’s manager, he handles logistics and general tasks as well as other business ventures. Everyone who surrounds Pitbull ends up in charge of one company or another. Calderon and Pitbull go over security for Pitbull’s performance at the World Cup in Brazil. There would be a helicopter and Navy Seals protecting him. Pitbull is pleased with this, which Calderon acknowledges with a small grin. Calderon also runs a site called shoppitbull.com, and he has numbers to report.

“The first day broke $13 grand, which is great,” says Calderon. “Because there wasn’t any advertisement for it, only on Twitter and Instagram.”

With Pitbull’s shiny tie and fuzzy, rapper-turned-entrepreneur-speak—everything’s a “call to action,” a “no-brainer,” or has to do with “monetizing” something or other—it’s easy to underestimate him. But Pitbull’s longtime music manager, Charles Chavez, says the smartest thing about Pitbull is that he knows what he doesn’t know. He’s gotten opportunities because of his music and has surrounded himself with advisers. And he keeps making more money. “He’s just more intelligent than the average artist,” says Chavez. “He’s always watching Bloomberg TV! It’s an ego-driven business, and most artists, it’s all about them. He understands he can’t do everything himself, and he soaks everything in.”

Calderon is done; next arrives Fernando Zulueta, a barrel-chested, deep-voiced businessman who works with Pitbull on his Miami charter school project. Zulueta has gray hair, a deep tan, and a large glass of red wine. Pitbull will be running his own New Year’s Eve special on Fox, and Zulueta suggests hiring the Black Eyed Peas for the night. They move on to a startup, a kind of Spanish-language YouTube, which Zulueta promises will be like Pitbull’s own TV station. Pitbull considers this and waves at the waitress for more water. The look on his face suggests he’s about to say something profound, and he delivers.

“Explain that to me—because you use generators to make power, right?” Zulueta laughs with a loud bark.

Pitbull continues, straight-faced. “When you become a generation—say, the MTV generation—that’s where you create your power.”

Zulueta purses his lips, trying to understand.

“The content fed the culture, the culture fed the generation. Everyone says content is king. But culture is everything. Content creates a culture—the Kardashians created a culture.”

“I got it,” says Zulueta, though it seems like he might not.

Pitbull has already moved on. In a few hours, he’s due to get an honorary degree from Miami’s Doral College and has to deliver an inspirational speech. Zulueta hands over a draft. It’s about 20 pages, and the type is huge. Even so, Pitbull is displeased. “This is too long,” he says, flipping through. “This isn’t me. I need this to be the real me.” Zulueta assures him he can do whatever he wants to the speech, and at that Pitbull goes upstairs—to a room? an office?—to edit the speech with Muzquiz. Over the next two hours, one by one, Pitbull’s associates leave, until it’s just me and the ancient waitress.

When Muzquiz finally comes down, he’s apologetic but explains the speech needed work. We head to the college. Instead of an Escalade or limo, there’s just a regular midsize sedan. Pitbull, sunglasses finally on, gets in, and a cloud of cologne fills the small car. He hammers away on his BlackBerry. “It’s just me and the president who use these now,” he jokes. He’s rereading his speech on the phone and seems a little nervous.

It’s silent except for when he gives his driver directions in Spanish and tells one of his guys that he’s ready for his iced coffee. As we near the school in central Miami, Pitbull starts spraying himself with more cologne. First his Pitbull fragrance, then a bit of Tom Ford, then some Pitbull again. He explains, “I mix it, and then depending on how the women react, I either mix the same ones again or try a different combination.”

On arrival at Doral, Pitbull is whisked away to don his graduation robes. His appearance is supposed to be a surprise, though some members of the local Miami press have found out. They always do—he’s their most famous son right now, and the city loves him. Reporters line up at the back door, waiting.

Doral is both a charter high school and a tiny college, and there are probably 300 attendees in the auditorium, parents and grandparents fanning themselves with programs. Intros are made, and a very sweet high schooler gives a speech about how “this isn’t the end, it’s just the beginning.” Then Zulueta gets up to introduce the mystery guest and recipient of Doral’s first honorary degree.

“I did what they said I couldn’t. I became what they said I wouldn’t, and because of very special people in my life who believed in me, that’s why I’m on this stage tonight.” Applause. “So with that said, I want to say thank you to my mother.” More applause, mostly from the women. “She’s someone who had to raise a man, a woman who made a man. But she’s someone who taught me the No. 1 lesson in life, which is: how to survive.”

On paper, it’s inspirational gibberish. But Pitbull’s delivery—the neat pauses between each clause, his staccato cadence—transcends the clichéd subject matter. The crowd is in it with him, rising and falling as he slows down and speeds up: He’s turned it into a radio-worthy rap. The 20-minute oration culminates in a rousing call to let loose: “I know you’re going to get off the chain, off the glass, off the flip, off the rip, off the everything, y’all going to turn it up.” There’s a term in electronic dance music called dropping the bass—it’s that moment when, after a brief letup, the beat returns full force, and everyone goes insane. The audience is waiting for him to finish, waiting for the bass to drop. And then it comes. “Y’all go to all the parties you want to go to, and I’m sure there’s going to be plenty of them. But there’s no party like this, right here, right now.” He is theirs, and they are his.

By Emma Rosenblum

Monday, August 25, 2014

Volvo Ocean Race: A $20 Million Test Of Sailing Endurance

At some point next year, Charlie Enright will be seriously rethinking his mission in life. He’ll be at the helm of a 65-foot carbon-fiber sailboat hurtling through the violent seas between Antarctica and Cape Horn, instinctively ducking his head as waves fly toward his face with the strength of a fire hose. At 40 knots, or close to 50 m.p.h., there’ll be no room for error as the boat charges forward, hour after hour.

“In parts of the Southern Ocean we’ll be doing everything we can to slow these things down,” said Enright, skipper of the 9-man crew sailing Team Alvemedica around the world in the latest edition of the Volvo Ocean Race.

The Volvo has long been a dream for Enright, 29, a champion sailor at Brown University who had a role in Roy Disney’s 2008 documentary “Morning Light.” He also happens to be the grandson of famed boat builder Clint Pearson, who introduced thousands of people to sailing in the 1960s and 1970s with then-newfangled fiberglass yachts. Along with fellow Brown alumnus Mark Towill, 25, Enright put together a crew and got funding from a Turkish medical-device manufacturer to mount a challenge in the race that Alvimedica Chief Cem Bozkurt calls “the Everest of sports.”

“In 2011 we decided this was an idea we wanted to commit to making a reality, and now here we are with a boat and a team,” Enright told me on the docks in Newport, shortly before he set off on a shakedown cruise across the Atlantic.

The boats will race from Alicante to Cape Town and from there to Abu Dhabi; Sanya, China; Aukland, New Zealand and around Cape Horn to Brazil and Newport before finishing in Gothenburg, Sweden. The race is expected to take 10 months and will cost the average team about $20 million, including the cost of shore crews who will move a pair of shipping containers full of supplies in leapfrog fashion in front of the boats.

The boats will race from Alicante to Cape Town and from there to Abu Dhabi; Sanya, China; Aukland, New Zealand and around Cape Horn to Brazil and Newport before finishing in Gothenburg, Sweden. The race is expected to take 10 months and will cost the average team about $20 million, including the cost of shore crews who will move a pair of shipping containers full of supplies in leapfrog fashion in front of the boats.

“The boats actually move faster than the containers,” Enright explained.

To drive down costs from previous years, the 65-foot, carbon-fiber boats are all the same – “down to the toothbrush and sunglass holders” Enright said – so teams have few opportunities to compete by spending more money on better technology.

The dart-shaped boats have broad, flat surfaces underwater so they can quickly rise to the surface and plane. The cabin tops have been redesigned to throw waves up and over the helmsmen standing on raised platforms near the stern of the boat, although Enright says the water now tends to hit right about forehead level.

Traditional sailboats have a solid keel with lead weight to hold them upright. Volvo 65s have canting keels, hinged arms with a lead bulb that can be swung 40 degrees from side to side to provide more stability at the cost of a complex system of hydraulic rams to move the keel. After years of tinkering, the hydraulic rams and swing joints appear to be durable enough to survive a circumnavigation of the globe.

Accommodations are sparse; sailors sleep in narrow berths when they can, eat prepared meals, and the head, or toilet, is a simple carbon-fiber bowl just ahead of the mast with a handheld spray nozzle to flush it.

Teams share a single repair crew to cut down on costs and are limited in the number of sails they can buy. Each team must make it around the world using a single mainsail, a huge, computer-shaped slab of synthetic fabric covering 1,700 square feet, or the floor area of a modest suburban home.

Since the equipment’s the same and the crew members are evenly matched in muscle power and endurance, one of the key differentiators will be navigation. The oldest crew member on Team Alvimedica is Will Oxley, 49, an Australian marine scientist who’s competed in four round-the-world races including guiding Camper to a second-place finish in the last Volvo Ocean Race in 2011-12.

Oxley will spend most of his time in the navigator’s station belowdecks, a dark space directly beneath the cockpit equipped with laptops and communications gear streaming in constantly updated weather forecasts he will use to chart the best course to make it to the next port.

Ocean navigation is a lot like financial management. Navigators rely on weather forecasts much like investment managers rely on earnings projections. In both cases those forecasts start out highly inaccurate and get more precise as they move closer to real time. Within a few hours, they’re spot-on, but by then it’s too late for a boat moving at 20 knots to exploit a fast-moving weather system 200 miles away. So much like a commodities trader or a bond manager, Oxley must develop a point of view long in advance about where the best winds will lie, then position the boat to take advantage of them as they develop.

Ocean navigation is a lot like financial management. Navigators rely on weather forecasts much like investment managers rely on earnings projections. In both cases those forecasts start out highly inaccurate and get more precise as they move closer to real time. Within a few hours, they’re spot-on, but by then it’s too late for a boat moving at 20 knots to exploit a fast-moving weather system 200 miles away. So much like a commodities trader or a bond manager, Oxley must develop a point of view long in advance about where the best winds will lie, then position the boat to take advantage of them as they develop.

He has 20 years of data to help narrow the odds of where high-velocity winds will show up on a particular leg of the race.

“We start off with what worked” in past races, he said, and then determine a corridor to maximize the chance of getting to the right winds first. “I have to have a very good reason to move out of that corrider,” he said.

As the oldest man on the boat by far, Oxley won’t spend as much time “on the handles,” as sailors refer to the coffee-grinder winches in the center of the cockpit. But he will endure a grueling schedule that allows him only four-and-a-half hours sleep in every 24, “and if I’m lucky I get that in three lots,” he said. Every five or six days he gets to splurge on a 90-minute nap.

“If you sleep too long you lose track of the picture,” he said.

For Alvimedica Chief Bozkurt, the race is an opportunity to get his company’s name out there as he prepares to enter the U.S. market. Bozkurt, a medical doctor, has built the company by diving into markets that industry giants like Johnson & Johnson JNJ +0.25% have largely abandoned, like cardiac stents coated with drugs to inhibit clotting. Founded in 2007, it has already grown to the fourth-largest interventional cardiac device maker in Europe. Bozkurt said he expects to pour 27% of top-line revenue into research and development this year to develop devices in close consultation with the physicians who use them.

“Being a very young company, our brand awareness, brand recognition is quite low,” he said. And thanks to the threat of litigation and pesky U.S. regulations on medical-device manufacturers, “we cannot directly advertise, so that is why we decided to go on sports sponsorships.”

Sailing is an appropriate marketing vehicle since it appeals to all ages and has an international audience, he said. Bozkurt sought out Enright’s less experience team because he wanted the youngest sailors and claims, on camera anyway, that he doesn’t have any expectations other than returning safely home.

“The first target they have in this race is to finish the race in one piece, in a healthy position,” Bozkurt told FORBES. “We’re not looking to win.”

By: Daniel Fisher

“In parts of the Southern Ocean we’ll be doing everything we can to slow these things down,” said Enright, skipper of the 9-man crew sailing Team Alvemedica around the world in the latest edition of the Volvo Ocean Race.

The Volvo has long been a dream for Enright, 29, a champion sailor at Brown University who had a role in Roy Disney’s 2008 documentary “Morning Light.” He also happens to be the grandson of famed boat builder Clint Pearson, who introduced thousands of people to sailing in the 1960s and 1970s with then-newfangled fiberglass yachts. Along with fellow Brown alumnus Mark Towill, 25, Enright put together a crew and got funding from a Turkish medical-device manufacturer to mount a challenge in the race that Alvimedica Chief Cem Bozkurt calls “the Everest of sports.”

“In 2011 we decided this was an idea we wanted to commit to making a reality, and now here we are with a boat and a team,” Enright told me on the docks in Newport, shortly before he set off on a shakedown cruise across the Atlantic.

Charlie Enright at the helm of Team Alvimedica (Photo credit: Sam Greenfield/Team Alvimedica)

On October 11, the fleet of identical 65-foot ocean racers will set off from Alicante, Spain on the first leg of the 40,000-mile race, which has been held every three years since 1973. For Enright and his young crew, it’s a chance to prove themselves in one of the toughest endurance contests in sailing. For Alvimedica, it’s an opportunity to raise the worldwide profile of its growing business selling drug-coated stents, catheters and other cardiac devices.

“The boats actually move faster than the containers,” Enright explained.

To drive down costs from previous years, the 65-foot, carbon-fiber boats are all the same – “down to the toothbrush and sunglass holders” Enright said – so teams have few opportunities to compete by spending more money on better technology.

Traditional sailboats have a solid keel with lead weight to hold them upright. Volvo 65s have canting keels, hinged arms with a lead bulb that can be swung 40 degrees from side to side to provide more stability at the cost of a complex system of hydraulic rams to move the keel. After years of tinkering, the hydraulic rams and swing joints appear to be durable enough to survive a circumnavigation of the globe.

Accommodations are sparse; sailors sleep in narrow berths when they can, eat prepared meals, and the head, or toilet, is a simple carbon-fiber bowl just ahead of the mast with a handheld spray nozzle to flush it.

Teams share a single repair crew to cut down on costs and are limited in the number of sails they can buy. Each team must make it around the world using a single mainsail, a huge, computer-shaped slab of synthetic fabric covering 1,700 square feet, or the floor area of a modest suburban home.

Since the equipment’s the same and the crew members are evenly matched in muscle power and endurance, one of the key differentiators will be navigation. The oldest crew member on Team Alvimedica is Will Oxley, 49, an Australian marine scientist who’s competed in four round-the-world races including guiding Camper to a second-place finish in the last Volvo Ocean Race in 2011-12.

Oxley will spend most of his time in the navigator’s station belowdecks, a dark space directly beneath the cockpit equipped with laptops and communications gear streaming in constantly updated weather forecasts he will use to chart the best course to make it to the next port.

(Photo credit: Dan Forster/Team Alvimedica)

He has 20 years of data to help narrow the odds of where high-velocity winds will show up on a particular leg of the race.

“We start off with what worked” in past races, he said, and then determine a corridor to maximize the chance of getting to the right winds first. “I have to have a very good reason to move out of that corrider,” he said.

As the oldest man on the boat by far, Oxley won’t spend as much time “on the handles,” as sailors refer to the coffee-grinder winches in the center of the cockpit. But he will endure a grueling schedule that allows him only four-and-a-half hours sleep in every 24, “and if I’m lucky I get that in three lots,” he said. Every five or six days he gets to splurge on a 90-minute nap.

For Alvimedica Chief Bozkurt, the race is an opportunity to get his company’s name out there as he prepares to enter the U.S. market. Bozkurt, a medical doctor, has built the company by diving into markets that industry giants like Johnson & Johnson JNJ +0.25% have largely abandoned, like cardiac stents coated with drugs to inhibit clotting. Founded in 2007, it has already grown to the fourth-largest interventional cardiac device maker in Europe. Bozkurt said he expects to pour 27% of top-line revenue into research and development this year to develop devices in close consultation with the physicians who use them.

“Being a very young company, our brand awareness, brand recognition is quite low,” he said. And thanks to the threat of litigation and pesky U.S. regulations on medical-device manufacturers, “we cannot directly advertise, so that is why we decided to go on sports sponsorships.”

Sailing is an appropriate marketing vehicle since it appeals to all ages and has an international audience, he said. Bozkurt sought out Enright’s less experience team because he wanted the youngest sailors and claims, on camera anyway, that he doesn’t have any expectations other than returning safely home.

“The first target they have in this race is to finish the race in one piece, in a healthy position,” Bozkurt told FORBES. “We’re not looking to win.”

By: Daniel Fisher

Thursday, August 21, 2014

How sports leagues use iBeacons to complement in-stadium SMS

Apple’s iBeacon technology increasingly excites marketers, especially those who see the technology as a way to drive responsive mobile experiences that delight visitors in sports stadiums and keep them loyal, but SMS still has an important role to play.

Fifteen months after its widely chronicled rollout, the platform’s early popularity also has called into question the need for SMS programs that have underpinned in-stadium marketing programs for years. However, the technologies’ differing strengths and weaknesses suggest iBeacons can be an extra tool that rounds out the fan experience.

“It’s not an either-or, it’s both,” said Mark Tack, vice president of marketing for Chicago-based Vibes, whose in-venue mobile marketing clients have included professional sports leagues. “IBeacons are the latest crave that’s captured a lot of fanfare and are getting a lot of publicity.

“IBeacons are great for the on-the-move fan and can provide timely content in just the right location,” he said. “But you also have the fan who is in their seat and text-message marketing is great to help advertisers of marketers and sports venues engage with fans on their mobile devices while they’re seated at an event.”

Selling points

Launched in mid-2013, iBeacon caused a stir with its ability to provide retailers and other small to medium enterprises with a way to target offers with pinpoint accuracy, as well as to simplify payments and enable on-site offers. Its low energy demands and low cost – as of May, iBeacon third-party manufactured hardware could be purchased for as little as $5 – also were big selling points.

IBeacon became the centerpiece of an Apple venture with Major League Baseball to develop an upgraded version of the league’s At the Ballpark application. The platform displayed welcome messages, exclusive content, maps and coupons according to fans’ locations within a particular stadium and the positioning of the beacons. Up till then, such precision targeting was not possible.

Today, iBeacon use at United States stadiums is growing. “The sporting experience is one where you need to stay relevant and continue to introduce something that’s new and exciting,” Mr. Tack said. “Every time the fans comes to the ballpark, you want to keep the experience fresh. All of the sports organizations have been early adopters for most mobile technologies.”

Warriors' app includes a raft of features to drive engagement.

The National Football League tested beacons during this year’s Super Bowl, and 20 baseball stadiums are adding them this year. In one of the first live rollouts of proximity beacon technology at a major sporting venue, in March, the NBA’s Golden State Warriors began to integrate proximity technology into their mobile application and the Oracle Arena, the club’s home since the mid-1960s.

“Beacon-supported proximity marketing is eclipsing geofence-based push companies because we can send a message when someone is in line for the men’s room, not just in the stadium,” said Alex Bell, co-founder of Sonic Notify, the Warrior’s proximity-technology partner. “We have proved with GSW [Golden State Warriors] that when done right, it does drive fan engagement.

“GSW saw a 69 percent increase in seat upgrade revenue via app after installing our proximity marketing solution,” he said.

In one promotion, first-time visitors to the team’s store received a mobile message about a coupon offer. Interacting with the message led to a video of Warriors player Harrison Barnes speaking directly to the fan.

When fans were asked “What are you looking at?” the answer was “a Harrison Barnes video, not a coupon, although the coupon was there,” per Mr. Bell.

Texting criticized as limiting

Mr. Bell is in the camp of those who criticize in-stadium texting programs at professional baseball, football and basketball games as too limited to drive fan engagement.

“Texting is too broad,” he said. “If there is no app to drive a consistent message then it is a one-time shot.”

“There are two magic things about proximity marketing that make it special,” he said. “The right time and place delivery and the fact that the delivery mechanism is the user’s own phone. In-stadium texting satisfies the second criteria but misses on the important first criteria.”

Warriors' digital strategy showcases iBeacon technology.

Those who fail to recognize the differences between iBeacon and SMS are missing an opportunity to reach customers with two powerful technologies.

“IBeacon is actually triggering content based on location,” Mr. Tack said. “So when we think of SMS, there’s a lot of ways you can use SMS which is full of content. When you compare a content technology to a trigger technology, it’s kind of comparing apples to oranges.”

Clients’ use of SMS

Among the ways Mr. Tack’s clients use stadium SMS programs is the ever-popular text-to-win invitation. “You can do an onscreen call to action using SMS,” he said. “The fan is sitting in his seat and in between innings on the Jumbotron or a huge sponsorship sign he sees a Verizon commercial or a Pepsi commercial or a McDonald’s commercial that says: ‘Text Big Mac to 84237 for your chance to win.’ That’s creating engagement for fans in their seats. There’s no iBeacon technology related to that.”

Voting on in-game action also remains a fan favorite. Between innings, an onscreen text might ask: What was your favorite play so far? And invite fans to text A, B or C one of three video highlights, showing the tally on screen.

“Text is also great for distributing mobile wallet content,” Mr. Tack said. “For example, ‘Text Pepsi to 84237 to receive a free Passbook or Google Wallet offer for the next inning only.’ Or ‘Only good for the next 20 minutes.’ The text message becomes the communication vehicle, the distribution vehicle of valuable content.”

Dynamic duo

Others see iBeacon playing a dynamic role alongside texting in mobile sports-marketing.

“There are great use cases for both,” said Blake Sirarch, vice president of design for Willow Tree Apps, which worked with the Barclays Center, home of basketball’s Brooklyn Nets, in developing the team’s app. In-stadium texting provides a one-to-one communication channel that makes it possible for venue operations personnel to respond to guest needs in real-time.

Beacons’ ability to disseminate targeted messages to a greater number of fans in a controlled way allowed the Barclays Center to use the technology to spread the word about news and upcoming events by placing beacons at points throughout the arena, he said. Fans are instantly prompted to sign up for the Barclays Center newsletter when they walk through the doors.

“The concept of iBeacons is an exciting one but the trick is getting people to engage with the promotion,” said Alex Jarvis, UK sales manager with Britain’s Boost Communications, which worked on soccer club Manchester City’s mobile program. “The US market is more open to this.

“In the UK we are less reluctant to participate in such engagements. I suppose like everything it depends on the details. If something is of interest you're going to engage with it.”

By Michael Barris

Tuesday, August 19, 2014

Roll of dice on Vegas comes up a big winner

NBA summer league grows into 'July Madness' for fans, budding young prospects